Radu Dudău, EPG Director

More than four months after the November 30, 2016 deal between OPEC and eleven non-OPEC producers to curb oil output from January 1 to June 30, 2017, the crude price is still stuck at around $50/bbl. The agreed production cuts were 1.8 million barrels a day (mb/d), out of which OPEC’s part was 1.2 mb/d.

From December to February, the global oil marker Brent hovered between $55/bbl and $57.5/bbl, only to see a new slump to below $51/bbl at the end of March, and then a relative recovery to $55 in the first week of April.

No doubt, the November 30 agreement has produced significant results. Prior to it, oil prices were spiraling down, threatening to return to the early 2016 levels, when Brent traded at less than $30/bbl. As indicated by IEA, the OPEC countries lost export revenues of about $450 billion in 2015, down from $1.2 trillion in 2012. In addition, global oil and gas upstream investment fell by a quarter in 2015, followed by another quarter in 2016. On the other hand, oil production costs have sunk massively over the past two years – 15% in 2015 and 17% in 2016, as estimated by IEA.

Early this year, however, the oil price rally entailed by the production cut agreement incentivized an increased output among the non-OPEC producers, with an especially noteworthy rebound of the US shale production.

In fact, as pointed out by Harvard’s Leonardo Maugeri, global oil production started speeding up already in October 2016 and culminated in December 2016 and the early weeks of January 2017. Over that time span, the US, Canada, Brazil and the North Sea had a combined increase of oil output of almost 1 mb/d compared to their September 2016 levels, while Russia hit a post-Soviet production record of 11.2 mb/d.

On the other hand, with insufficient global demand prospects to absorb such a production growth, a glut has built on the international oil markets.

According to OPEC’s Monthly Oil Market Report of March 2017, the cartel’s total crude production, according to secondary sources (i.e., trades and inventories assessed by independent consultants and analysts) decreased from 33.0 mb/d in January to 32.1 mb/d in February and to 31.9 mb/d in March 2017.

Interestingly, Saudi Arabia’s output, according to secondary sources, fell from 10.44 mb/d in January to 9.86 mb/d in February and to 9.79 mb/d in March 2017, while according to Riyadh’s direct communication, it increased from 9.75 mb/d in February to 10.01 mb/d in March, adding to market pressure. The Saudi Oil Ministry attributed the increase to technical reasons, including oil moving into storage.

In the US, oil rigs were added for the 12th consecutive week, reaching 672 currently active oil rigs – a 90% increase year-on-year and the highest level since August 2015, according to Financial Times.

At the beginning of April, Riyadh raised its official selling prices to the US for the month ahead, while cutting them to every other region, thus targeting US oil inventories. This was yet another bold step taken by Saudi Arabia to bolster its effort of rebalancing the market, albeit with the associated risk of irking its paramount customer.

After the American cruise missile strike on Syria on April 6, the Brent price jumped by about 2% to above $56/bbl, because of worries of supply disruptions. Nevertheless, that price spike was short-lived, with no discernible concerns on the market that oil supplies would be disrupted on the longer term. The Brent barrel settled at $55.2 on April 6, up 0.6% on the day. Nonetheless, although there is no threat of oil supply disruption, the Syria strike raises worries about the future of coordination on oil policy between Russia and Saudi Arabia.

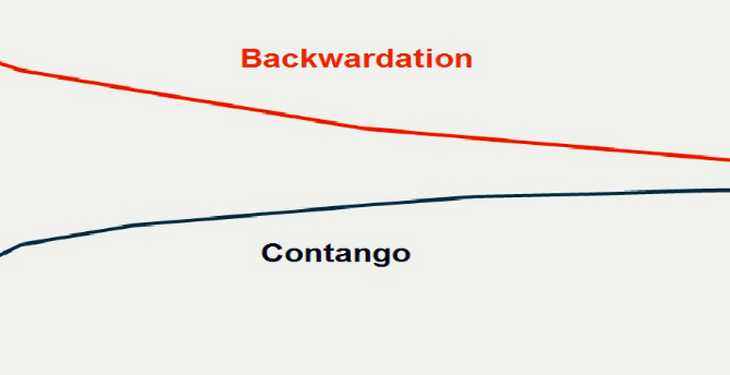

Underlying this oil price volatility, a fundamental market indicator regards how the short-term oil contracts compare to the longer-term ones. Shortly after the November 30 deal on output curbs, short-term prices began to strengthen versus longer-term futures. Thus, over the course of January, front-month Brent deliveries narrowed their discount versus year-ahead futures, upon expectations that the supply curbs would tighten the market.

A situation in which longer-term futures are more expensive than shorter-term ones is known as contango in market lingo. When the oil market is in contango, storage becomes a lucrative, low-risk business of collecting storage fees and selling stored oil forward at a profit. Contango has been the defining situation on the global oil markets since mid-2014.

By mid-February 2017, the front-month Brent contracts became only 16 cents less expensive than the seven-month futures. A situation in which prompt deliveries are more expensive than longer-term ones is called backwardation. In fact, it is also emphatically called normal backwardation, as it describes the „normal” dynamics of a balanced market, on which profits cannot be made by simply amassing oil stockpiles and selling them forward. As oil inventories draw down, the price of prompt oil deliveries tends to trade above future prices.

However, short of reaching proper backwardation, the spread between prompt delivery and futures has since widened again in favor of the latter, reaching in April about 80 cents between the front-month and the seven-month Brent futures.

OPEC itself included among the effectiveness criteria of the output curbs a move to market backwardation, given the cartel’s interest in drawing down the oil stocks and clearing the glut.

But the question is, can the global oil glut be reined in by OPEC’s production cuts? In other words, can the market return to backwardation – and if so, would backwardation be economically stable, as the US shale producers and others are ramping up their output?

Some pundits are skeptical about such a prospect. As their argument goes, the increased oil production within OPEC from October to December 2016 and the output growth in non-OPEC countries thereafter, combined with the slowdown of demand growth in China and India make it likely that the global market will remain glutted – and in contango – throughout the better part of 2017. According to this line of thought, the odds are that oil prices will stagnate and even go through occasional slumps.

In its latest monthly oil report, IEA somewhat optimistically sees diminished oil inventories in Q1 2017, with the market tightening and „very close” to coming into balance. At the same time, against a background of weaker than expected demand and of non-OPEC supplies increased by 485,000 b/d this year, oil oversupply can well persist throughout the year, according to IEA.

On the other hand, there are important market players which are already betting that the days of oil oversupply will soon be over and that, consequently, the market will move into balance – and hence that backwardation will return.

Since January, the top five global oil traders – Glencore, Vitol, Gunvor, Mercuria and Trafigura – have sold or have been seeking to sell important parts of their stakes in oil storage firms. Surely, they must be expecting that OPEC will extend its output cuts into the second half of 2017, and that this will be effective, which would thus help draw down global inventories and bolster oil prices.

Regardless of how decisive such a move by OPEC will turn out to be, it certainly makes sense for the global traders to hedge their previous bet on contango.