Europe and the United States are part of the war in Ukraine, through the military, logistical and intelligence support they give to the authorities in Kiev, as well as through the unprecedented economic sanctions imposed on Russia, with the declared objective of forcing it to stop its attacks and to give up its occupation of the neighboring state. Russia’s hydrocarbons retained a special status for themselves during the first 14 days of the conflict: Europe continued to import oil and gas from Russia, which continued to receive hard currency. Moreover, the whole context, as well as the general perception of this paradoxical situation, pushed oil and gas prices to ever-higher levels, thus increasing the gains for sanctioned Russia and the burden on the European Union economies, the enforcers of sanctions.

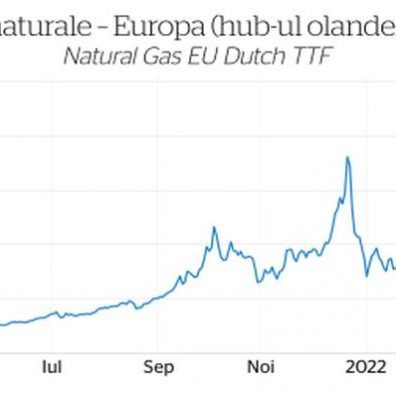

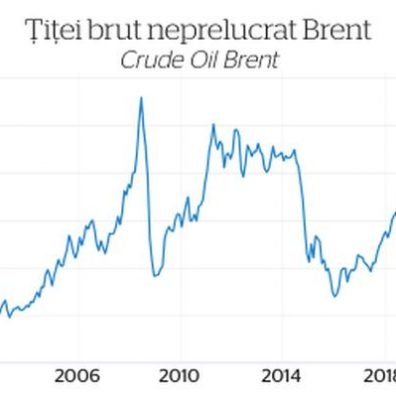

The widespread feeling is that this situation cannot continue and it seems only a matter of time before either the European Union or Russia decides to stop the transit of hydrocarbons. We are now at a Brent crude oil price of 126 dollars per barrel in futures contracts, having reached 139 dollars per barrel, the highest since 2008, when Russia invaded Georgia and the price of crude oil was over 140 dollars per barrel. EU gas prices climbed to 267 euros per MegaWatt-hour (euro/MWh), after temporarily reaching an all-time high of 345 euro/MWh.

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19

The first peak gas price in Europe was reached in October 2021 (114 euro/MWh, about 5 times higher than the usual level of the previous 8 years). On 21 December 2021, the price reached 181 euro/MWh, and then fell rapidly to around 65 euro/MWh in mid-February. It was almost triple the average of previous years, but understandable, at least in part, by the impact of the rapid post Covid-19 recovery which boosted demand to levels that EU suppliers and traders were not prepared for. The mild winter seemed to reduce pressures and there were hopes that spring and the easing of economic policy differences between the EU and Russia could help stabilise prices at levels placed by analysts between 35 and 50 euros/MWh.

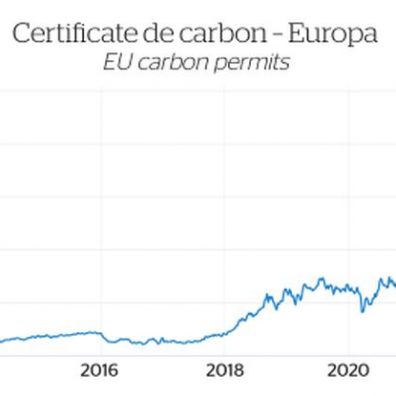

The impact of carbon certificates and the EU’s decarbonisation measures and massive investments for the transition to a green society were still included in the analyses. There was talk, for example, of “greenflation” – the inflation caused by the Green Deal. And there were some real arguments, if only because the price of allowances reached more than 94 euros per unit on 31 January, a level almost four times higher than two years earlier, after two series of accelerated rallies (November 2021-May 2021, a roughly threefold increase, and October 2021-February 2022, an almost 50% increase). Today, probably influenced by the uncertain outlook for the European economy, the price of carbon allowances hovers around 60 euros per unit, with a forecast of 69 euros for the end of the first quarter of 2022.

IMPACT OF THE WAR

The invasion of Ukraine by the Russian military cut the price of carbon allowances by 35% in 2 weeks. In the same period, the price of benchmark crude oil in Europe rose by almost 40%, from 90 to 125 dollars/barrel. Natural gas in Europe (benchmark TTF) climbed from 62 euros/MWh on 21 February to 267 euros/MWh 2 weeks later as Russia threatens to block supplies and the EU and US discussed cancelling purchases from Russia. In response to Germany’s decision to halt the Nord Stream 2 pipeline certification process, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said his country has the right to take an equivalent decision and impose an embargo on gas flowing through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline.

THREATS AND PREPARATIONS

Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that the US is working with European allies to examine the “prospect” of banning Russian oil imports. Germany has expressed reluctance to ban Russian energy imports, while South Korea has said it is unlikely to join energy sanctions. Bulgaria supports sanctions against Russia as a means to stop its invasion of Ukraine, but will likely seek an exception on a ban on Russian gas and oil imports if such a proposal is put forward. Bulgaria is almost entirely dependent on gas supplies from Gazprom, and its only oil refinery, owned by Russia’s LUKOIL, supplies more than 60% of the fuel used domestically.

Markets were also hit by reports of a possible delay in the resumption of the nuclear deal with Iran, which would have released some additional quantities into the global market.

SOLUTIONS FOR NOW

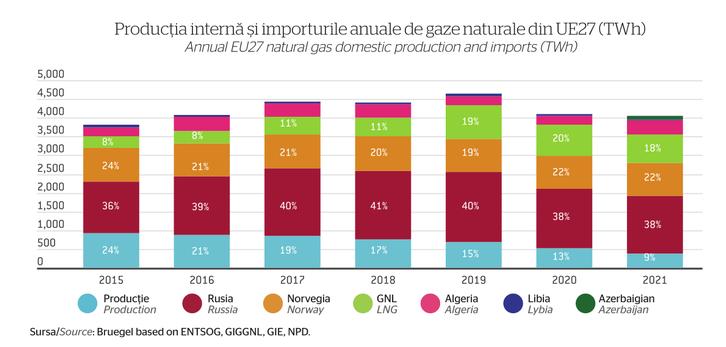

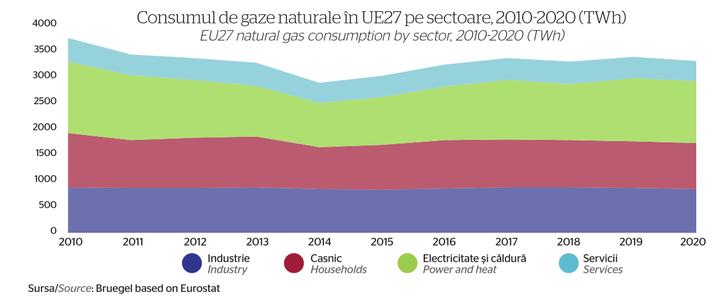

According to a Bruegel analysis, if Russian gas stops flowing, measures to replace supply won’t be enough. The European Union will need to curb demand, implying difficult and costly decisions. Although the EU has sought to reduce its dependency on Russian natural gas imports for years, Russia continues to supply around 40% of EU gas consumption.

This winter almost through, the worst case scenario was avoided. The risk of exceptionally cold temperatures has not materialized and the contractual supplies by Russia continued, with 18 TWh/week. It was also helpful that imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) strongly increased to 80 terawatt hours (TWh) in the first 24 days of January 2022, compared to 60 TWh in the first 24 days of December 2021. As a result, at the beginning of March, the storage in EU were near 27% full according to GIE – AGSI. The level is the lowest in years, but not exceptionally low, as even lowest percentages were recorded in 2018, 2015 and 2014.

“However, the picture becomes more complicated when the intricacies of individual economic, technical and political gas markets across the EU are considered”, wrote Bruegel experts. We saw the example of Bulgaria, above. As a rule, “the central and eastern European pipeline system is designed to bring imports from the east to final consumers. Despite investment in reverse-flow capacities and new pipelines, if too much gas were to come from the west, pipeline bottlenecks could prevent sufficient deliveries to the easternmost parts of the EU or Ukraine”, shows the analysis from Bruegel.

OPTIONS FOR NEXT WINTER

For the near future, existing infrastructure allows additional import volumes from Norway and North Africa, and additional LNG volumes, which together could displace current (low) imports from Russia. From another perspective, International Energy Agency – IEA calculated that “a suite of measures spanning gas supplies, the electricity system and end-use sectors, could result in the EU’s annual call on Russian gas imports falling by more than 50 billion cubic meters (bcm) within one year – a reduction of over one-third. These figures take into account the need for additional refilling of European gas storage facilities in 2022 after low Russian supplies helped drive these storage levels to unusually low levels”.

Adding other possibilities for Europe to go even further and faster to limit near-term reliance on Russian gas, such as delaying the coal phase-out, among others, would mean a slower near-term pace of EU emissions reductions, but would reduce the near-term Russian gas imports by more than 80 bcm, or well over half, calculated IEA.

To avoid entering the next winter with low storage, as happened this winter, Europe’s average storage should be at least 80% by 30 September 2022, decided the European leaders. The Commission will propose a mechanism to ensure action is taken if storage rates are not sufficient to reach that target. It is also considering proposing a legal requirement for EU countries to ensure a minimum level of storage is achieved by 30 September each year.

SHAPING THE FUTURE WITHOUT RUSSIAN GAS

For the future, accelerated electrification based on renewables and curbing demand are the solutions on the table. With respect to the latter, most natural gas is used for heating, in industrial processes and for producing electricity and district heat. In all three areas there is potential to reduce demand, all experts agree. Replacing thermal plants with renewable power generation, by accelerating the deployment of new wind and solar projects, will address the main gas consumption sector in Europe. All the same, maximizing power generation from existing dispatchable low-emissions sources, especially nuclear will also reduce gas consumption.

A measure beneficial for both the industry and the residential sectors is boosting the near-term rate of building retrofits and heat pump deployment for improved energy efficiency. IEA also mentioned the opportunity of public awareness campaigns meant to encourage behavior changes in homes and commercial buildings such as adjusting heating controls in Europe’s gas-heated buildings. “The average temperature for buildings’ heating across the EU at present is above 22°C. Adjusting the thermostat for buildings heating would deliver immediate annual energy savings of around 10 bcm for each degree of reduction while also bringing down energy bills”, urged IEA.

—————————————-

This article first appeared in the printed edition of Energynomics Magazine, issued in March 2022.

In order to receive the printed or electronic issue of Energynomics Magazine, we encourage you to write us at office [at] energynomics.ro to include you in our distribution list. All previous editions are available HERE.